This will be a discussion for oil cooling, in which there are two main ways to cool oil. Engine oil, transmission oil, hydraulic oil, power steering oil, differential oil, and even shock oil can and will need cooling. We will focus on engine oil cooling in this article but the two cooling methods apply to any heat rejection application, each with their positives and negatives. There is not a lot of information regarding either of these methods, the positives, the negatives, or why sometimes they work and other times they do not. We want to help bring light to this somewhat “black art” of cooling the engine oil. The information we are pulling from is gathered from over decades of experience as engineers for the world’s leading cooling system supplier for motorsports. Working with ALMS, to Tudor World Series, to NASCAR, IndyCar, F1 and Trophy Trucks, we have firsthand cooling experience at the pinnacle of multiple motorsports ventures.

Why does Engine oil heat up? Engine oil serves two functions, to lubricate the engine and to remove heat from components that coolant cannot (IE under the piston, rods, crankshaft, cams, etc). As a result, engine oil heats up from both friction and internal combustion increasing temperatures of the engine.

Typical Oil Temperatures:

Before diving into how to cool the oil, we feel it necessary to express the large misconception with oil temperature that seems rampant within the aftermarket community and even some race series. Engine oil temperature IS NOT engine coolant temperature. Coolant temperature in passenger cars is generally kept between 180-215 degrees Fahrenheit (85-100 Celsius) with some reaching up to 230 (110 C) safely. Some race series run coolant temperatures up to 260 degrees Fahrenheit (127 C); however, these engines are designed to handle this without distorting the block or cylinder head. Engine oil, on the other hand, is expected to reach much higher temperatures! Anyone telling you otherwise should be questioned intently. Engine oil needs to reach *at least* 100 degrees C (212 degrees F) to burn off condensation (water) build-up within the engine *which is perfectly normal and happens in every single engine*. If oil does not reach this temperature, the oil is unable to do its job to the best of its abilities and increased engine wear will result. It is a wise assumption to believe oil temperature sampling is anywhere between 85-95% of the hottest points in the engine, which means engine oil needs to be 85-95 degrees Celsius to burn off condensation.

So what temperature can you run in your car/engine?

That is quite a loaded question and near impossible to answer without a lot of testing. We can give it our best shot, though. Most passenger cars are perfectly fine with oil temps up to 240-260 degrees F *utilizing the OEM recommended oil weight*, with some being designed to handle temps up to 315 Degrees F and higher! How can this be? Standard oil these days have flash temps well over 200 C (400 degrees F), and as long as there is sufficient oil pressure, the oil does not care what temperature it is at. That being said, utilizing an OEM engine and OEM clearances, we would suggest sticking to the OEM oil weight up to around (240-250 Deg. F). If it makes you feel safer, run a bit thicker oil but with thicker oil, comes increased engine wear at cooler temperatures and increased heat into the oil through more friction and less flow (flow and pressure are

How can we get rid of this heat?

There are two ways to reduce the heat that is transferred into the oil. Oil to water (or O2W for short) transfers the oil’s heat into the engine’s coolant system through a unit typically called a heat exchanger. Another route is oil to air (or O2A for short), which transfers the oil’s heat through an exchange with airflow through a unit typically called an oil cooler. Both of these systems can be implemented incorrectly and work poorly, both of these systems can be implemented correctly and work great. Individual applications tend to favor a certain method over the other but ultimately that decision should be an end user choice as each person has his or her own goals, objectives, and ideals. Both can and will work great when properly executed.

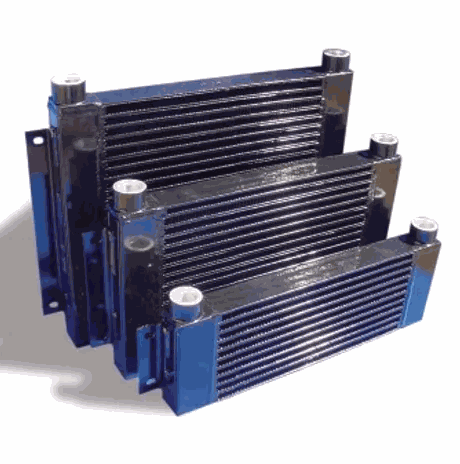

Air to Oil (A2O) Oil Coolers:

These are the units you see on the front of cars and are generally square in shape and not that large. These use ambient air to cool the engine oil which flows through small tubes with internal

Positives:

Extremely simple design and operating principle

Easy to implement

on a wide range of applicationsCosts are generally reasonable

Large delta T (change in temperature) for increased heat rejection

Wide range of possible locations for mounting

Negatives:

Performance is highly dependent on airflow.

Airflow is highly dependent on coolant stack pressure differential, which increases from adding another heat exchanger (engine oil cooler) to the stack.

With higher coolant stack pressure, flow through ALL UNITS is decreased.

You can see a reduction in radiator performance from adding an oil cooler.

When placed in front of other heat exchangers (radiator), hotter air is now reaching the radiator, reducing efficiency even further/

Pinhole leaks from rocks are possible.

Highly recommended to run a thermostat on the engine oil cooler to reach operating temperatures quicker, increasing costs.

Very easy to over-cool the engine oil with an

improper setup system.Lines are typically long and increase the pressure drop of the system.

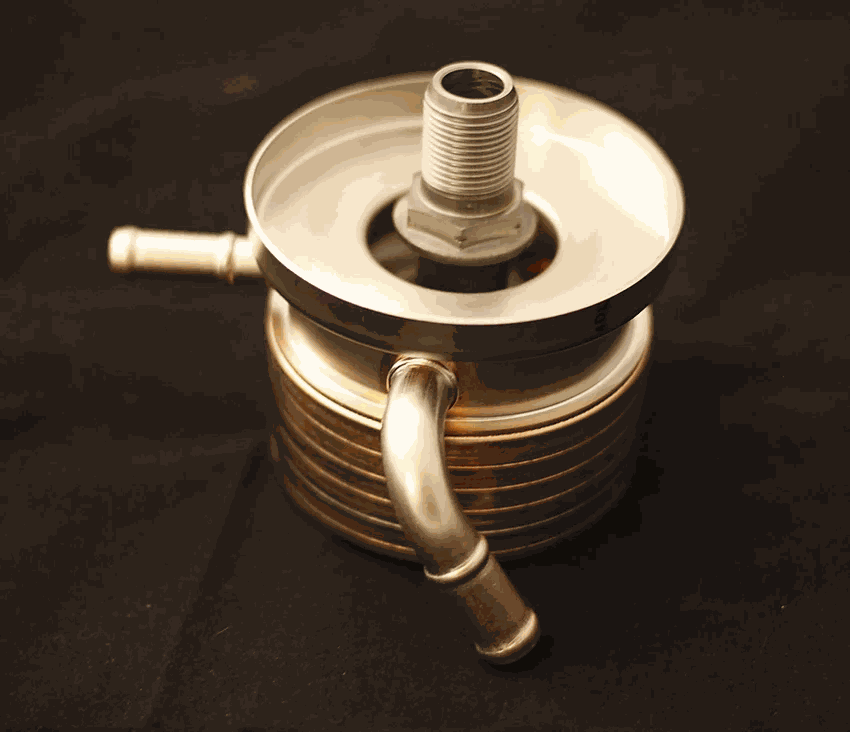

Oil to Water (O2W) oil coolers:

These are the units generally found on OE applications where engine oil cooling is necessary. Utilizing the engine’s coolant to heat the oil quickly during the initial start and to cool the oil when the engine oil reaches operating temperature, this system is quite ingenious and reduces cold start wear and hot running wear. However, it comes with its own pitfalls of course, just like nearly all designs, compromises are necessary. Typically they utilize a portion of the engine’s coolant flow which surrounds internal

Positives:

Ability to be packaged in small spaces

Ability to be packaged without any airflow consideration

Heats up oil when beneficial and cools oil when beneficial automatically by design

Does not require a thermostat

Very low chance of leaking

Great at regulating an adequate temperate for proper oil operation

Does NOT add a unit to the cooling stack, thereby decreasing delta P for the cooling stack as compared to O2A

Negatives:

These systems are generally more expensive as they are typically application-specific.

Inputting more heat into an already taxed coolant system can lead to overheating.

Due to the lack of delta T, the engine oil temperature will likely be higher than O2A counterparts unless airflow is an issue.

Possibility to leak oil into the coolant system or coolant into the oil system.

Conclusion:

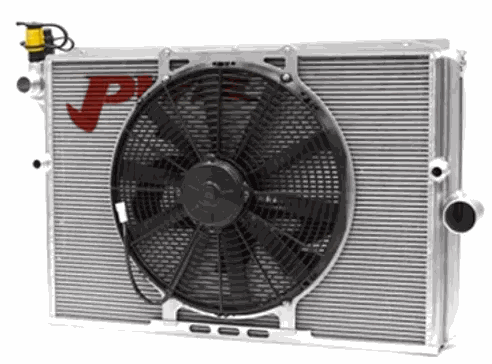

We have witnessed *both styles* successfully used in nearly every motorsports venue. That being said, if ultimate oil cooling is required, an O2A is still recommended though typically much larger than what is commonplace in the aftermarket community and *behind* the radiator (see below photo). For those that drive their cars on a normal basis, off track, we would strongly urge you to look into O2W units as they offer a lot of positives geared towards daily driving. When airflow is hard to come by, we would also recommend looking into O2W as reducing airflow through the radiator can be very detrimental. Systems have to be looked at as a whole and not just single entities.

Regardless of which style you utilize, please keep in mind that temperatures below 100 degrees C are not recommended and can actually be detrimental to engine health in the long run.

As always, please let us know if you have any questions and we will do our best to answer.

Oil Cooling - A Deeper Look